Design And Performance Lab

|

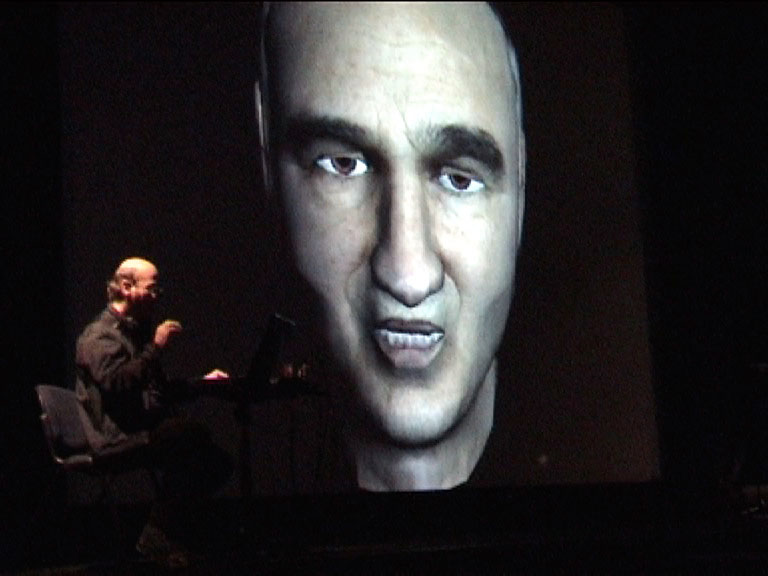

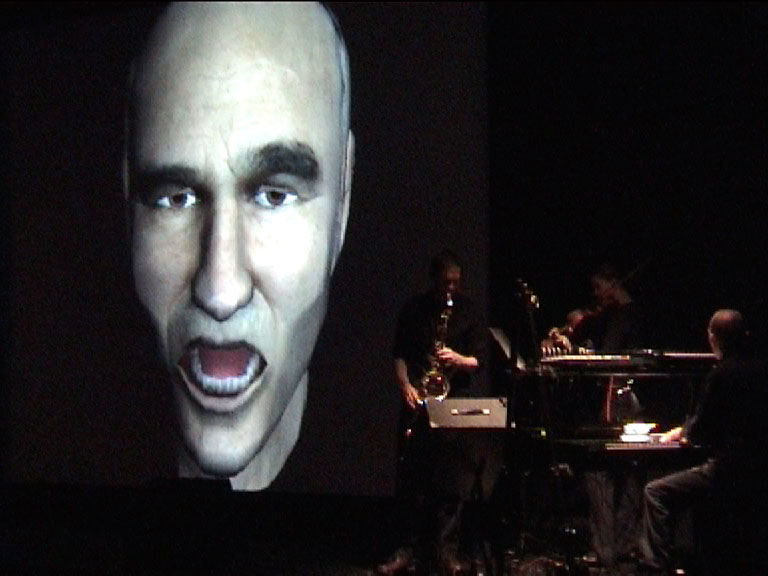

The Singing Head Stelarc. ScreenPlay Games Festival Broadway Cinema, Nottingham February 28, 2004 (c) 2004 Johannes Birringer

Videogames play a hugely successful role in the marketplace of popular culture and entertainment. Their venues range from arcades and pubs to the computer screen at home; their players can be found in all age groups and classes; they are solitary aficionados or congregate in massive online games (MMOG) played by teams or "tribes." Game culture has had a multi-layered and vibrant evolution in the four decades that video and computer games have been around - a history which parallels the rise of television and the personal computer. As the global market is ever- expanding, it is hardly surprising that its impact as a cultural formation is now studied, and its relations to the history of technology, film, animation, music, performance and art recognized. University programs pay attention, and so do museums. Nottingham's "ScreenPlay" Festival, now in its fourth edition, announces itself as an annual cross-over event for "games makers, thinkers and players," and one of its strengths is its joyfully eclectic programming embedded in a relaxed and playful environment. Housed by Broadway Cinema and organized by Frank Abbott (Nottingham Trent University), Rasheeqa Ahmad (Broadway) and a team of volunteer helpers, the festival has grown since its beginnings; it invites audiences to "play with your mind," to explore "games in our lives and in our digital culture," i.e. it looks at the intersections of old and new, commercial and independent games, art and technology, animation and electronic music, staging tournaments and design competitions along with critical seminars, film screenings, webcasts and performances. While the local dadaist Reactor troupe invaded the Cinema's cafbar on the final night with a hilarious grand-guignol performance ("GHAOS_ZK: Return of the Egg Box"), a good-natured spoof on the standard game design of virtual 3D worlds, another interactive performance featured a collaboration between Australian body artist Stelarc and jazz musicians Jan Kopinski (saxophon), Jana Kopinska (viola), and Steve Iliffe (keyboards, samplers). Presented in the main auditorium, this was a jam session of the third kind, a surreal show with moments of great eloquence and others closer to Medusa's smile of the grotesque. Stelarc, who became known in the 70s for his excruciating body suspensions, hanging from hooks that perforated his flesh body, recently developed even more notorious work with technological and robotic apparatuses which penetrate, append or activate the body or wire its flesh and muscle to the internet. Much talked about in academic discourses on the cyborg and the "posthuman," Stelarc continues his practice of bodily performance, except that now the "body" is in quotation marks, merged with technologies and sensors or supplanted by intelligent agents. At Screenplay, he performed with an avatar, an intelligent agent physically modeled after his head and equipped with a data-base, voice-activated lip-synching and animated facial expression. In normal circumstances of exhibition, this prosthetic device, which is in fact the animated projection of a giant head, automatically responds to visitors who interrogate it via a keyboard. The "Prosthetic Head" appears to be somewhat informed and somewhat intelligent. If you enter your name, it will remember you and address you by your name. It might also say: "you look tired today, June." If you ask it a metaphysical question, it will provide a metaphysical answer, or it may even play a bit with your expectation and offend you. Brimming with customary joviality and morbid irony, Stelarc afterwards introduced the head and commented on its moodiness and on the sexiness of artificial intelligence, especially now that advanced programming allows the head to "learn" (act as an emergent, self-organizing system) and act on its "own" as an autonomous entity for which Stelarc is not responsible. On this occasion, however, Stelarc tried to enter scripted commands to the "Prosthetic Head" (PH) to make it perform in concert with the live musicians, and the ensuing interactivity soon reached its limits since it was false and counterintuitive from the beginning. Apart from the obvious fact that PH cannot sing, has no musicality and cannot improvise with or respond to the musicians playing their instruments and creating a rich tapestry of sonic and rhythmic phrasings, there is much to be learnt from this concert in regard to current artistic pretensions in the world of interactivity. Interactive design for playable art, as we now see it in digital installations and net.art, is clearly modeled upon game design and the dexterous use of game consoles by a player. The structure of games, with its rules and objectives, its narrative worlds of quests and pursuits, deaths and rebirths, its competitive energy, learning curves, rewards and punishments, has aesthetic and functional dimensions, and of course social, psychological and ideological ones. But on a basic level the cybernetic theory behind interactive systems implies a feedback loop, a mutual responsiveness or action-between. Or the simulation of such action-between. In sonic installations and interactive dance, the intrinsic experience of the fluid, changing media environment (image, sound, digital objects) depends on the physical interface, the movement-activity which is sensed by sensors or motion tracking cameras controlling the response-behavior of the system. In the ScreenPlay concert, the jazz musicians play live with their acoustic and amplified instruments. The live music they create can also be modulated and electronically manipulated as all three musicians play with feedback/delay pedals or samplers. But they see PH on the big screen next to them and can react to what its amplified voice says. Stelarc sits at his laptop across the stage, and while he obviously enjoys "playing" the scripting options - which elicit a variety of alphabetic or phrase responses from the PH database - almost like a conductor, one also senses a certain embarrassment. The head exists in its closed-off artificial world, and it can perform logical, programmed operations based on algorithms. It had not been programmed to sing, yet Stelarc and the musicians decided to use four different kinds of language phrasings or articulations paired with different music. The sequence of these four "songs" was no doubt fascinating, even if the artificial head began to repeat itself, loop itself, too soon, exasperatingly, to engage us on any emotional or intellectual level, or any level approaching complexity. The concert thus thrives on the paradoxical, and maybe some audience members in fact did feel emotionally or viscerally touched by the contradictory synchronicity of the living, breathing sound of saxophone and string instrument with the utterly synthetic speech engine of PH. The Head sounds robotic, but as an artificial agent, dressed up as a floating face that looks like Stelarc's, it has a fragile, almost vulnerable holographic presence: it is a voice-mask, hiding its blindness and deafness, its insensitivity. Perversely, PH begins to sound like 1970s Kraftwerk music with a computer-generated monotonous voice repeating words over a techno beat. But there is no techno beat here, but incongruously traditional jazz.

The force of repetition, as in games which rely on it to enhance obsessional dedication, perhaps even converts the whole incongruous scenario I have described: PH's iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii, uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu, and oooooooooooooooooooooo (song 1) or its more rhythmic alterations of monosyllables, vowals and consonants (song 3) strikes us as reassuringly alien in spite of the simplicity and banality. A friendly robot, not the sinister or menacing kind Stanley Kubrick created with HAL. When PH begins its charming pychobabble in song 2 ("I'm not intentional, I'm just a headÉÉI'm not intuitive, I'm just a headÉ.), or when it speaks code in the last song ("usic/td/trtr_rr/lstein> I don't know /td_dd/tr/exe/td/genderÉ.."), it is no longer the synthetic process that is pathetic but the live music. With its organic ebb and flow, its increasingly complex variations on the theme, its echoes and motifs refracted in intense dramatic outbursts and increases of tempo, dynamics and volume, the music appears out of scale and proportion. Jazz as a dialogic medium, and masterful language of improvisation, is too complex. When Kopinski and his band paint a landscape of somber moods, full of melancholic evocation, and I look up and see PH bare its teeth ("uuuuuiohssssst"), I suddenly find myself in the wrong movie, with David Lynch rehearsing a scene where HAL learns the onomatopoeia of dispassion, the slow repetitions of synthesis, beyond human concern and regardless of subjective longing or belonging. A cloning genesis of language, before song. Strangely, it is in the pauses, the gaps, and the sudden bursts (consonants change pitch), that the prosthetic speaker actually appears musical to us, we want him to be musical, perhaps have a gender that corresponds to Stelarc's, without that "it" would know that or understand the desire. We imagine it to have timing, which it doesn't, and we want it to hear the other musicians, which it cannot. It is Stelarc at the laptop, in this case, or the musicians, who create the illusion that the prosthesis is learning to hit a note at the right time or to feel the yearning expressed through Kopinska's bow. But there is no interactivity between prosthetic instrument and musicians, only between Stelarc and the data-base his programmers have created for the head. Stelarc, perfectly fitting for the ScreenPlay festival, played his own game, already a step ahead of us. Video stills: J.Birringer

|